- ATR and Fly91 Sign New Eight-Year Global Maintenance Agreement

- Global Aircraft Hangar Door Specialist Jewers Doors deepens India Commitment with New Subsidiary

- Air India enters multi-year agreement with Boeing for component services program to support entire 787 fleet

- Air India converts 15 Airbus A321neo orders to latest generation A321XLR

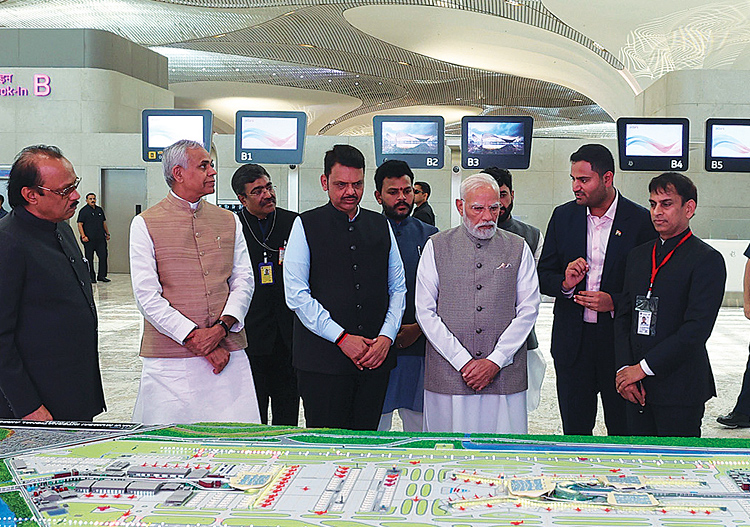

India's Airport Boom!

The question is no longer how fast India can build airports, but whether its development model is delivering a smoother, more resilient aviation system

India is building airports at an unprecedented pace, commissioning roughly one every 50 days. On paper, this reflects ambition and readiness for a future where India becomes the world's third-largest aviation market. Yet passengers at major metro hubs continue to face long queues, terminal congestion, delayed baggage, overcrowded security checkpoints and strained last-mile connectivity.

The contradiction is stark, while the number of airports has multiplied, the lived experience of flying especially through Tier-1 hubs has improved only marginally. At the same time, several newly commissioned regional airports remain underutilised, operating with low frequencies and sparse passenger traffic. This raises a critical question. Has India's airport development model prioritised asset creation over system efficiency, passenger comfort and network integration?

MORE AIRPORTS, SAME BOTTLENECKS

India's metro airports, especially Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Chennai continue to absorb the bulk of passenger traffic. Despite the proliferation of Tier-2 and Tier-3 airports, congestion at these hubs remains chronic.

Shantanu Gangakhedkar, Principal Consultant and Commercial Aviation Lead, Frost & Sullivan, explains the structural mismatch clearly, "There is a big difference between building hubs and having strong connectivity to those hubs. Though in the past few years India has built many new hubs, the majority of routes have largely remained the same... expanding existing airports should also be looked at apart from only building new hubs."

In essence, the problem is not the absence of airports, but the persistence of airline network concentration. Routes continue to converge around major hubs because that is where demand, connectivity and commercial viability remain strongest.

Suman Ramasundaram, senior aviation leader and former Head of Airport Planning and Development at BIAL, adds that congestion is not just an infrastructure issue, but a planning and regulatory challenge, "Currently Indian airports are not governed by uniform, enforceable Service Level Agreements (SLAs) beyond what is specified in individual concession agreements... Just when one terminal is inaugurated, the future expansion plans are getting drawn out."

She further highlights the limitations of global design standards, "Most major airports are planned in line with IATA's ADRM norms. However, these standards do not fully capture India-specific realities such as additional security layers, higher manpower requirements, large proportion of first-time flyers, and culturally distinct passenger behaviour." As a result, terminals may be compliant on paper but feel overcrowded in practice, especially during peak traffic banks.

NIGHT-TIME CONGESTION AND OPERATIONAL PRESSURE

Another structural factor intensifying congestion is India's 24-hour airport operations and the clustering of international flights during early morning hours. Ramasundaram explains that metro airports face intense terminal pressure between 2 am and 4 am due to international arrival banks driven by airline network dependencies, bilateral constraints, crew rotations and slot availability. This concentration is shaped by airline economics rather than airport planning, resulting in short-duration but extreme stress on immigration, baggage systems, ground transport and terminal flow.

While the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) and BCAS implemented operational interventions after public outcry in late 2022, many were ad hoc and later relaxed. However, Ramasundaram notes, "The MoCA along with AERA has now initiated work on a formal SLA framework for major airports with ongoing performance monitoring. Once implemented, this has the potential to significantly improve passenger comfort and service quality, particularly at high-traffic metro hubs."

ARE NEW AIRPORTS IMPROVING THE PASSENGER JOURNEY?

The Civil Aviation Minister's statement that India is building one airport every 50 days reflects remarkable construction momentum. But how much of this translates into smoother journeys? Surabhi Rana, Head of Air Service Development at Noida International Airport, offers a nuanced, data-backed view, "The impact of India's airport expansion is most visible in non-metro and emerging city pairs. Over the past few years, a significant share of domestic traffic growth, over 60 per cent in some periods, has come from Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities." She emphasises that this is not merely about convenience, "This is not just about access, it is about inclusion."

However, both Gangakhedkar and Ramasundaram caution that geographic access alone does not equate to smoother journeys. Gangakhedkar further goes on to explain: "There are two parts to this. First, making air travel accessible to Tier-3 and Tier-4 cities will take time before strong demand emerges. Second, most connectivity is still with key Tier-2 airports, so congestion is not necessarily reducing, at least for now."

Reinforces her point, Ramasundaram adds, "New airports improve geographic access for certain catchments, but smoother journeys depend more on flight frequency, airline reliability, landside connectivity and operational maturity than on the mere existence of airport infrastructure." In short, airports are necessary, but not sufficient for better passenger experience.

WHY ARE REGIONAL AIRPORTS UNDERUTILISED?

Low utilisation of several newly commissioned regional airports is one of India's most visible aviation challenges. Gangakhedkar describes this as a demand-cycle issue, "The demand for these locations is still very sparse and cyclical. It will take a few years till we see these new airports in smaller cities see higher demand."

Rana views early underutilisation as natural, "Regional airports are long-term assets, and early underutilisation is a natural phase in market development." She also highlights the importance of diversified revenue, "From an airport perspective, viability increasingly depends on diversifying revenue streams beyond aeronautical revenue. Cargo, logistics, aircraft parking, MRO support and commercial land development can significantly improve sustainability."

Bringing a sharper economic lens, Ramasundaram states, "The primary issue is demand and propensity to fly... Infrastructure does not drive O/D demand. Airports will only facilitate connecting traffic, provided airline operators with relevant business models exist." This reinforces a critical reality - airports cannot manufacture demand; airlines, economies and network strategies must converge to create it.

ARE NEW AIRPORTS COMMERCIALLY VIABLE OR POLICY-DRIVEN?

India's newer airports are often positioned as tools for regional development and social inclusion. But are they being built with long-term commercial sustainability in mind? Gangakhedkar takes a balanced view, "Airports play a very crucial role in economic development. The critical aspect is how well these airports are utilised and managed so that there is steady traffic growth to support sustainable and profitable operations."

Rana agrees that policy support is essential early on, but long-term success is commercial, "Passenger volumes, airline networks and non-aeronautical revenue performance ultimately determine success." "Many newer airports are policy-driven assets aimed at regional development rather than immediate commercial viability... without wellstructured PPP models and balanced concession agreements, airports risk becoming financially stressed assets," Ramasundaram adds offering her more direct assessment:

WHY DO METRO AIRPORTS REMAIN CONGESTED?

Despite decentralisation efforts, metro airports remain the country's dominant gateways. "Tier-1 airports are very well-connected leading to continuous and growing demand, resulting in airlines continuing to prioritise these airports," Gangakhedkar explains. He adds that shifting airline networks is operationally complex due to ground handling, catering, turnaround capabilities and cost structures.

Rana sees metro congestion as a reflection of economic gravity rather than decentralisation failure, "Metro congestion reflects strong economic concentration and network depth rather than a failure of decentralisation." She further stresses the need for system-level planning, "This highlights the need for a shift from airport-by-airport expansion to network-based planning."

Offering a rather blunt opinion, Ramasundaram says, "Congestion at metro airports fundamentally reflects demand concentration... Building airports ahead of demand does not decongest metro hubs; it creates parallel infrastructure that may remain underutilised."

ARE CURRENT INVESTMENTS SUFFICIENT FOR 2030?

With India's passenger traffic expected to more than double by 2030, are current investments sufficient? "Yes," says Gangakhedkar, noting that new airports are planned to support demand for the next 20 years and beyond. However, he cautions that existing hubs must also be prepared for the next five years through expansion or seamless connectivity.

However, Rana warns that the challenge is not whether new airports are being built, but whether investments in comfort, efficiency and passenger experience can keep pace."

Ramasundaram outlines three urgent priorities, "India-specific planning approaches, Regulatory alignment and Targeted investment strategy." Without this, she cautions, Indian airports risk persistent congestion at metros.

CONCLUSION

India's airport development story is impressive, but incomplete. The country has mastered the art of building infrastructure. What it now needs to master is orchestrating the systemaligning airports with airline networks, designing for India-specific passenger behaviour, integrating landside connectivity, and enforcing service standards that scale with demand.

As experts consistently highlight, congestion is not merely a capacity problem; it is a planning, network, regulatory and demand-distribution problem. Regional airports are not failing because they exist, but because demand maturation takes time. Metro airports are not congested because decentralisation has failed, but because economic gravity still pulls traffic into a few hubs.

The next phase of India's aviation journey must move from counting airports to optimising experience, from asset creation to system performance, and from policy-driven expansion to commercially sustainable aviation ecosystems. Only then will India's aviation growth translate into smoother journeys, better connectivity and a globally competitive assenger experience.